In an era of accelerating climate change, few California cities are as vulnerable to wildfire as Berkeley. Nestled at the base of the East Bay Hills, with dense vegetation, historic homes, and narrow, winding roads, the city faces mounting risks from wind-driven embers—tiny, flaming particles that can ignite structures far from an active flame front. Recognizing this danger, Berkeley has taken a bold step by adopting a new wildfire mitigation ordinance known as EMBER: Effective Mitigations for Berkeley Ember Resilience.

The EMBER ordinance is a landmark piece of legislation that aims to reduce ignition risk and increase the fire resilience of Berkeley’s residential neighborhoods, especially those on the urban-wildland interface. The ordinance will go into effect on January 1, 2026, for properties in designated high-risk areas. EMBER introduces a new regulatory framework that governs defensible space, enforces inspections, and encourages structural upgrades to mitigate wildfire exposure. Its passage marks a turning point for homeowners, buyers, and real estate professionals alike—particularly those with ties to the city’s hillside districts.

What the EMBER Ordinance Requires

At its core, EMBER is about creating what wildfire scientists call “Zone 0”— a five-foot buffer around a home where flammable materials must be cleared. Studies from recent California fires have shown that embers landing in this perimeter are one of the primary ignition sources during structure loss events. As a result, the ordinance bans anything combustible within that five-foot zone: wooden fences that touch the home, mulch, dry vegetation, stored firewood, even certain types of plastic containers or decor.

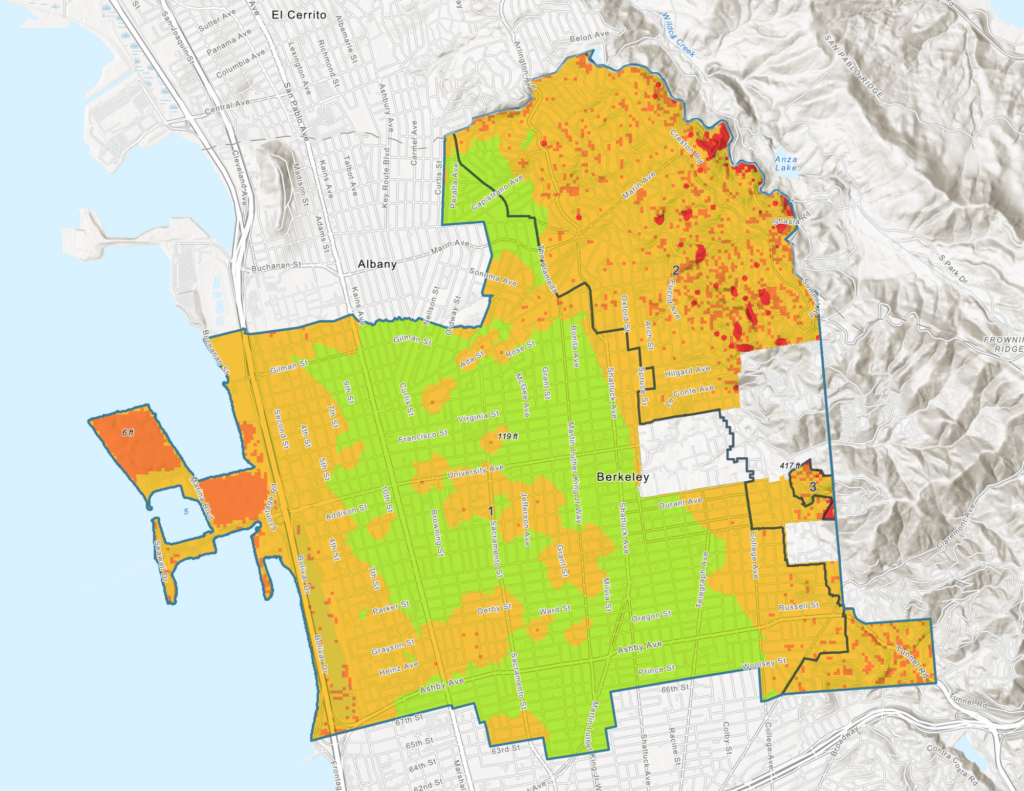

Here’s an important clarification: Zone 0, as defined in the ordinance, refers specifically to the five feet immediately surrounding a structure. This should not be confused with Fire Zone 3, which is part of the geographic area of the city identified by the Berkeley Fire Department as having elevated wildfire risk. These Fire Zones determine where the EMBER ordinance will initially apply.

Zone 1 is the flats, Zone 2 is the lower Berkeley hills, and Zone 3 is the area around Panoramic Hill. The city is also proposing the creation of a new Zone 4 risk area that will run between Grizzly Peak Boulevard and Wildcat Canyon Road and will be the first region targeted for “Zone 0” compliance.

Unfortunately, the overlapping terminology—“Zone 0” versus “Zone 3”—has led to some confusion. It might have been clearer if the city had used distinct naming conventions to differentiate between the building-level buffer zone and the broader risk classification zones.

In addition to defensible space, EMBER gives the Berkeley Fire Department new enforcement powers. Fire prevention staff will begin conducting annual inspections in the affected zones. If violations are found, property owners will have a minimum of 60 days to comply before fines are issued—escalating to as much as $500 per day for repeat or ongoing violations. However, as clarified by the final June 2025 ordinance, citations will only be issued after multiple notices, and enforcement will emphasize education and support. Misdemeanor charges were removed from the final ordinance, and homeowners with work in progress will not be penalized.

While the law stops short of mandating retrofits like ember-resistant attic vents, Class A fire-rated roofs, or dual-pane tempered windows, it strongly encourages these upgrades. A working group of residents, scientists, and stakeholders is expected to review and recommend updates to vegetation guidelines by the end of 2025. The city has also secured a $1 million grant from Cal Fire and is using revenue from Measure FF to offer subsidies to income-qualified homeowners.

Which Homes Are Affected

In its initial phase, EMBER will apply to roughly 900 homes located in the highest fire hazard zones identified by the Berkeley Fire Department. Specifically, this includes properties in and around Panoramic Hill, the Grizzly Peak Firebreak area (the proposed Zone 4 area), and neighborhoods that border Tilden Regional Park. These areas are characterized by steep terrain, abundant vegetation, and limited evacuation routes, all of which elevate their wildfire vulnerability.

Homes in these zones were selected based on topography, fire history, and proximity to wildland fuels. While the current scope is limited, the city has indicated that EMBER requirements will likely expand to additional neighborhoods over time, especially as wildfire risk modeling continues to evolve. That said, no official timeline for expansion has been announced.

Homeowners can consult detailed fire zone maps provided by the City of Berkeley to determine whether their property is in an affected zone. The city also plans to conduct direct outreach and provide an online lookup tool in the months leading up to enforcement.

Financial and Logistical Impact on Homeowners

For many homeowners, EMBER presents both logistical challenges and new expenses. The cost of bringing a property into compliance will vary depending on the existing landscape and layout, but city officials estimate the average expense to be between $2,000 and $5,000. Structural retrofits—while optional—could add significantly more, especially for older homes with outdated materials.

The city has promised financial support for low- and moderate-income residents, and some funding is available through existing climate resilience and fire prevention programs. Additional assistance may include transfer tax credits, free fire-resistant gutter guards and vent mesh, and potential support through pending state legislation such as AB888 and the Firewall Act. Nevertheless, the up-front costs may be burdensome for middle-income homeowners who don’t qualify for assistance and may not have immediate access to liquidity for upgrades.

On the flip side, compliance may provide insurance benefits. With many insurers pulling out of California’s fire-prone markets or raising premiums dramatically, EMBER-compliant homes may be better positioned to retain coverage. While not guaranteed, it’s likely that insurers will begin to recognize compliance as a mitigating factor—especially if other cities adopt similar programs and a new baseline for resilience emerges. Some Berkeley homeowners have reported receiving insurance discounts—ranging up to around 25%—after completing Zone 0 mitigation and home hardening work.

Real Estate Market Implications

For the Berkeley real estate market, EMBER could be both a disruptor and a differentiator. On the one hand, homes that are already compliant—or easily brought into compliance—may gain market appeal. Buyers relocating from fire-prone parts of California are increasingly prioritizing safety, defensible space, and insurability in their purchase decisions. Sellers who invest in EMBER-compliant upgrades may be able to position their homes as “fire-ready” and command a premium as a result.

On the other hand, homes that fall short of the new requirements could face headwinds. If buyers anticipate high compliance costs—or uncertainty around inspections and fines—they may be less willing to pay top dollar. Agents may begin to include EMBER readiness in listing disclosures, just as they do with sewer laterals, BESO energy reports, or seismic retrofitting. It’s also possible that lenders and underwriters will take EMBER zones into account during loan approval and insurance clearance processes.

Importantly, EMBER may also reshape neighborhood dynamics. Some buyers may shy away from hillside neighborhoods entirely in favor of lower-risk areas like Central Berkeley or South Berkeley. This could flatten or even dampen price growth in the hills while increasing competition for homes in denser, flatter zones that lie outside current fire hazard boundaries.

Striking a Balance Between Safety and Equity

Like many progressive policies, EMBER walks a fine line between public safety and homeowner burden. The ordinance is grounded in strong fire science, and the threat it addresses is real. But it also risks widening the gap between wealthier residents—who can quickly bring their homes into compliance—and those who face financial or logistical hurdles.

The city has emphasized a commitment to equity, with outreach efforts, grant funding, and partnerships with local nonprofits to assist vulnerable residents. Still, how EMBER is implemented—and how transparently enforcement is carried out—will ultimately determine whether it becomes a model for climate resilience or a source of division.

Looking Ahead

Berkeley’s EMBER ordinance is among the first of its kind in California and may well become a template for other communities in the wildland-urban interface. It represents a shift in how we think about homeownership—not just as a private investment, but as part of a collective infrastructure of resilience.

For now, homeowners in affected areas have time to prepare. Inspections will not begin until May 2026, giving residents nearly a full year to complete mitigation work. A grace period of at least 60 days will follow each inspection before any fines are considered. But as the climate continues to shift, the urgency behind EMBER is only going to grow. In a state where fire season is becoming a year-round phenomenon, EMBER is a reminder that adapting to risk isn’t optional—it’s essential.